Hashtag Medicine: Coronavirus Fear Goes Viral on Social Media

Hashtag Medicine: Coronavirus Fear Goes Viral on Social Media

Last week, the World Health Organization sent out a series of tweets explaining why they weren't yet ready to declare the 2019-nCov outbreak a global health emergency. The organization's Twitter account was immediately flooded with hundreds of negative comments spouting mistrust, misunderstandings, and misinformation.

Many Twitter users questioned the organization's motives, accusing them of allowing the illness to spread. Other tweeters claimed the Chinese government was deliberately withholding information and that thousands were dying on the streets of Wuhan, the city where the virus was first diagnosed. Still others maintained the illness was genetically engineered by the US government.

WHO has since declared the virus a global and national health emergency, but perhaps the only thing that has gone more viral than the pathogen itself is the chatter it has generated on social media.

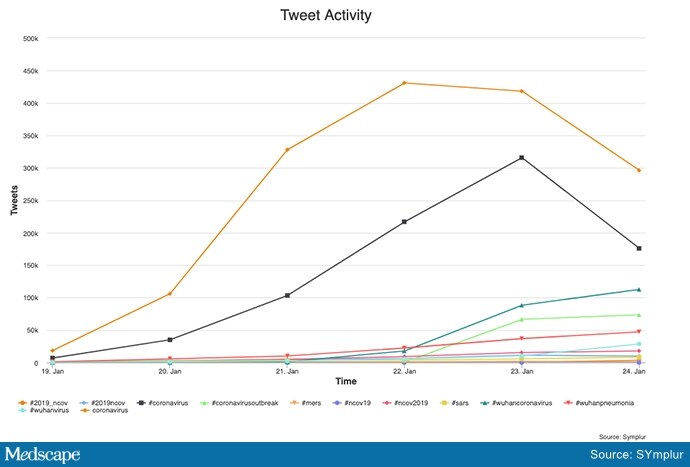

During the week of January 19th, when the coronavirus broadly entered the public consciousness, Symplur, a healthcare social media monitoring tool, collected more than 1.2 million tweets on the topic — with nearly 700,000 Twitter users participating in the online conversation and more than 30 associated hashtags in play.

However, Tom Lee, one of Symplur's cofounders, noted that the volume of tweets relating to the coronavirus is considerably higher than the data they've captured. The volume of tweets has been so high — the system has collected up to 442,000 per day since the start of the outbreak — they are not able to process them all.

"We are only looking at a fraction of the action taking place on Twitter," Lee told Medscape Medical News. "We throttled back to pull in a random sample representing about 10% of the current activity."

Meanwhile on Facebook, more than 50 coronavirus pages have popped up. The "Coronavirus Warning Watch," for example, is a private group that quickly attracted over 1000 members and an average of 270 posts per day. Members appear to use the page to swap unsubstantiated claims and share links for protective gear like face masks that are of questionable benefit.

That a large percentage of the social media posts reviewed by Medscape express unease and conspiracy theories isn't surprising to David Ropeik, a former Harvard professor and author of the book, How Risky Is It, Really? Why Our Fears Don't Always Match the Facts (McGraw Hill, 2010.)

"Our brain's first reaction to a potential new risk like a coronavirus, particularly if we don't have a lot of information yet, is not careful cognitive thought because that takes too long. If we pondered over a poisonous snake we'd be dead, so we respond quickly," Ropeik told Medscape Medical News.

While humans have always been prone to the amplification of initial snap judgements, social media gives them a bullhorn and a method to quickly and easily share their thoughts, Ropeik said. He noted a similar pattern of social media hysteria over Ebola and Zika several years ago, despite the tiny risk of exposure to the average person.

The spread of disinformation on the various platforms is nothing new either, Ropeik pointed out. Fake accounts known as "bots" and troublemakers known as "keyboard trolls" often jump into a trending conversation to fearmonger and create a false narrative. Their goal, Ropeik said, is to create a sense of doubt about the institutions that are supposed to protect us and leave us feeling concerned for our safety, however irrationally.

Scammers further confuse people by offering fake cures. A flurry of posts currently making the rounds links to a 10-year-old debunked study that suggests oregano cures coronavirus infection. Add to this, silly memes like puppies wearing face masks and the heavily used #coronabeervirus hashtag that erroneously associates the virus with a popular Mexican beer brand.

In the offline world, the number of confirmed cases of 2019-nCoV is rising, nearing 10,000 worldwide, according to the January 31st WHO statistics. While most diagnosed and suspected cases are in China, the virus has spread to 19 other countries. The US has confirmed six cases: two in Illinois, two in California, one in Arizona, and one in Washington state, the CDC reported. Deaths worldwide have surpassed 200.

Together, misinformation and mixed messages raise the danger that reputable voices like WHO, Health and Human Services (HHS), and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) will be drowned out.

Yet, social media companies do seem to be making an attempt to prioritize accurate information.

Facebook's third-party fact checkers have examined the huge number of claims about the coronavirus and are flagging the inaccurate posts so they don't show on top of users' feeds, the company said in a statement. Twitter announced on Monday that it had tweaked its algorithm so that US users who search for coronavirus-related hashtags will be redirected to the CDC account. They're also ensuring that searches on coronavirus-related hashtags in other countries bring up information from reliable sources. Other platforms, including YouTube, say they are considering similar steps.